With some of the free time I had, I decided to remake a video game from my childhood. Though the game was rendered with 3D visuals, it was essentially a 2D game. I’ll need to detect collisions when two actors in the game occupy the same footprint. The footprints will usually be rectangular. But these rectangles could be oriented in any way. Detection of orthognal overlapping bounding boxes is a simple matter of checking if some pointes are within range. But if they are not oriented parallel/perpendicular to each other, then a different check must be done.

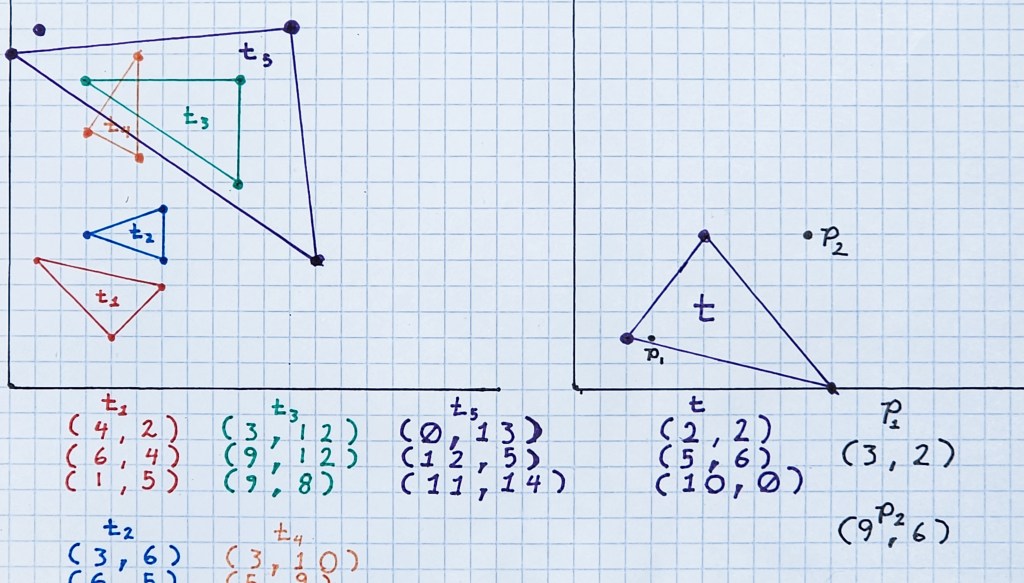

Rectangles can be constructed with two triangles. The solution to detecting overlapping rectangles is built upon finding intersection with a triangle. Let’s look at point-triangle intersection first. Let’s visualize some overlapping and non-overlapping scenarios.

Examining this visually, you can intuitively state whether any selected pair of triangles or points intersect with each other. But if I provided you only with the points that make up each triangle, how would you state whether overlap occurs? An algorithmic solution is needed. The two solutions I show here did not originate with me. I found solutions on StackOverflow and RosettaCode. But what I present here is not a copy and past of the solutions. They’ve been adapted some to my needs.

For my points and triangles, I’ll use the following structures.

struct Point

{

float x;

float y;

};

struct Triangle

{

Point pointList[3];

};

There are lots of ways to detect whether a point iw within a triangle. Before writing my own, I found a simple one on GameDev.net. This is an adjusted implementation.

float sign(Point p1, Point p2, Point p3)

{

return (p1.x - p3.x) * (p2.y - p3.y) - (p2.x - p3.x) * (p1.y - p3.y);

}

bool pointInTriangle(Point pt, Triangle tri)

{

float d1, d2, d3;

bool has_neg, has_pos;

d1 = sign(pt, tri.pointList[0], tri.pointList[1]);

d2 = sign(pt, tri.pointList[1], tri.pointList[2]);

d3 = sign(pt, tri.pointList[2], tri.pointList[0]);

has_neg = (d1 < 0) || (d2 < 0) || (d3 < 0);

has_pos = (d1 > 0) || (d2 > 0) || (d3 > 0);

return !(has_neg && has_pos);

}

Usage is simple. Passing a point and a triangle to the function pointInTriangle results in the return of a bool value that is true if the point interacts with the triangle.

Point p1 = { 5, 7 };

Point p2 = { 3, 4 };

Point p3 = { 3, 3 };

Triangle t1 = { { { 2, 2 }, { 5, 6 }, { 10, 0 } } };

std::wcout << "Point p1 " << (pointInTriangle(p1, t1) ? "is" : "is not") << " in triangle t1" << std::endl;

std::wcout << "Point p2 " << (pointInTriangle(p2, t1) ? "is" : "is not") << " in triangle t1" << std::endl;

std::wcout << "Point p3 " << (pointInTriangle(p3, t1) ? "is" : "is not") << " in triangle t1" << std::endl;

Having Point-Triangle intersection is great, but I wanted Triangle-Triangle intersection. I decided to use an algorithm from RosettaCode. The code I present here isn’t identical to what was presented there, though. Some adjustments have been made, as I prefer to avoid using explicit pointers to functions. My definition of Triangle and Point are expanded to accomodate the implementation’s use of indices to access the parts of the triangle. By unioning the two definitions, I can use either notation for accessing the members.

struct Point

{

union {

struct {

float x;

float y;

};

float pointList[2];

};

};

struct Triangle

{

union {

struct {

Point p1;

Point p2;

Point p3;

};

Point pointList[3];

};

};

The algorithm makes use of the determinate function, an operation from matrix math. I’m going to skip over explaining the concept of determinants. Explanation of matrix operations deserves its own post.

inline double Det2D(const Triangle& triangle)

{

return +triangle.p1.x* (triangle.p2.y- triangle.p3.y)

+ triangle.p2.x * (triangle.p3.y - triangle.p1.y)

+ triangle.p3.x * (triangle.p1.y - triangle.p2.y);

}

Another key attribute of this implementation is that it optionally usually enforces the angles of a triangle being provided in a counter-clockwise order. If they are always passed in the same order, there is an opportunity for faster execution of the code. I chose general usability over speed. But I did mark the code with attributes to suggest that the compiler optimize for them being passed in that order.

void CheckTriWinding(const Triangle t, bool allowReversed = true)

{

double detTri = Det2D(t);

[[unlikely]]

if (detTri < 0.0)

{

if (allowReversed)

{

Triangle tReverse = t;

tReverse.p1 = t.p3;

tReverse.p3 = t.p1;

tReverse.p2 = t.p2;

return CheckTriWinding(tReverse, false);

}

else throw std::runtime_error("triangle has wrong winding direction");

}

}

The original algorithm had a couple of functions that were used to check for boundary collisions or ignore boundary collisions. I have expanded them from 2 functions to 4 functions. Whereas the original structured often as three points that are arbitrarily passed to a function, I prefer to pass triangles as a packaged structure. There is a place in the algorithm where a calculation is formed on a triangle formed by two points of one triangle and one point of the other triangle. The second forms of these functions accept points and will create a triangle from them.

bool BoundaryCollideChk(const Triangle& t, double eps)

{

return Det2D(t) < eps;

}

bool BoundaryCollideChk(const Point& p1, const Point& p2, const Point& p3, double eps)

{

Triangle t = { {{p1, p2, p3}} };

return BoundaryCollideChk(t, eps);

}

bool BoundaryDoesntCollideChk(const Triangle& t, double eps)

{

return Det2D(t) <= eps;

}

bool BoundaryDoesntCollideChk(const Point& p1, const Point& p2, const Point& p3, double eps)

{

Triangle t = { {{p1, p2, p3}} };

return BoundaryDoesntCollideChk(t, eps);

}

With all of those pieces in place, we can finally look at the part of the algorithm that returns true or false to indicate triangle overlap. The algorithm checks each point of one triangle to see if it is on the interior or external side of each edge of the triangle. If all of the points are on the external side, then no collision has been connected. Then it does the same check swapping the roles of the triangles.If any of the points are not external to the opposing triangle, then the triangles collide.

bool TriangleTriangleCollision(const Triangle& triangle1,

const Triangle& triangle2,

double eps = 0.0, bool allowReversed = true, bool onBoundary = true)

{

//Trangles must be expressed anti-clockwise

CheckTriWinding(triangle1, allowReversed);

CheckTriWinding(triangle2, allowReversed);

//For edge E of trangle 1,

for (int i = 0; i < 3; i++)

{

int j = (i + 1) % 3;

[[likely]]

if (onBoundary)

{

//Check all points of trangle 2 lay on the external side of the edge E. If

//they do, the triangles do not collide.

if (BoundaryCollideChk(triangle1.pointList[i], triangle1.pointList[j], triangle2.pointList[0], eps) &&

BoundaryCollideChk(triangle1.pointList[i], triangle1.pointList[j], triangle2.pointList[1], eps) &&

BoundaryCollideChk(triangle1.pointList[i], triangle1.pointList[j], triangle2.pointList[2], eps))

return false;

}

else

{

if (BoundaryDoesntCollideChk(triangle1.pointList[i], triangle1.pointList[j], triangle2.pointList[0], eps) &&

BoundaryDoesntCollideChk(triangle1.pointList[i], triangle1.pointList[j], triangle2.pointList[1], eps) &&

BoundaryDoesntCollideChk(triangle1.pointList[i], triangle1.pointList[j], triangle2.pointList[2], eps))

return false;

}

if (onBoundary)

{

//Check all points of trangle 2 lay on the external side of the edge E. If

//they do, the triangles do not collide.

if (BoundaryCollideChk(triangle2.pointList[i], triangle2.pointList[j], triangle1.pointList[0], eps) &&

BoundaryCollideChk(triangle2.pointList[i], triangle2.pointList[j], triangle1.pointList[1], eps) &&

BoundaryCollideChk(triangle2.pointList[i], triangle2.pointList[j], triangle1.pointList[2], eps))

return false;

}

else

{

if (BoundaryDoesntCollideChk(triangle2.pointList[i], triangle2.pointList[j], triangle1.pointList[0], eps) &&

BoundaryDoesntCollideChk(triangle2.pointList[i], triangle2.pointList[j], triangle1.pointList[1], eps) &&

BoundaryDoesntCollideChk(triangle2.pointList[i], triangle2.pointList[j], triangle1.pointList[2], eps))

return false;

}

}

//The triangles collide

return true;

}

The basic usage of this code is similar to the point collision. Pass the two triangles to the function

Triangle t1 = { Triangle{Point{3, 6}, Point{6, 5}, Point{6, 7} } },

t2 = { Triangle{Point{4, 2}, Point{1, 5}, Point{6, 4} } },

t3 = { Triangle{Point{3, 12}, Point{9, 8}, Point{9, 12} } },

t4 = { Triangle{Point{3, 10}, Point{5, 9}, Point{5, 13} } };

auto collision1 = TriangleTriangleCollision(t1, t2);

std::wcout << "Triangles t1 and t2 " << (collision1 ? "do" : "do not") << " collide" << std::endl;

auto collision2 = TriangleTriangleCollision(t3, t4);

std::wcout << "Triangles t3 and t4 " << (collision2 ? "do" : "do not") << " collide" << std::endl;

auto collision3 = TriangleTriangleCollision(t1, t3);

std::wcout << "Triangles t1 and t3 " << (collision3 ? "do" : "do not") << " collide" << std::endl;

With that in place, I’m going to get back to writing the game. I can now check to see when actors in the game overlap.

Finding the Code

You can find the code in the GitHub repository at the following address.

https://github.com/j2inet/algorithm-math/blob/main/triangle-intersection/triangle-intersection.cpp

Posts may contain products with affiliate links. When you make purchases using these links, we receive a small commission at no extra cost to you. Thank you for your support.

Mastodon: @j2inet@masto.ai

Instagram: @j2inet

Facebook: @j2inet

YouTube: @j2inet

Telegram: j2inet

Twitter: @j2inet