While implementing a few projects I decided to implement them in HTML since it would work on the broadest range of my devices of interest. My projects of interest needed to discover additional devices that are connected to my home network. I used

SSDP for discovery.

SSDP (Simple Service Discover Protocol ) is a UDP based protocol that is a part of UPnP for finding other devices and services on a network. It’s implemented by a number of devices including network attached storage devices, Smart TVs, and home automation systems. There are a lot of these devices that expose functionality through JSON calls. You can easily make interfaces to control these devices. However, since the standards for HTML and JavaScript don’t include a UDP interface, how to perform discovery isn’t immediately obvious. Alternatives to SSDP include having the user manually enter the IP address of the device of interest or scanning the network. The latter of those options can raise some security flags when performed on some corporate networks.

For the most part, the solution to this is platform dependent. There are various HTML based solutions that do allow you to communicate over UDP. For example, the BrightSign HTML5 Players support UDP through the use of roDatagramSocket. Chrome makes UDP communication available through chrome.udp.sockets. Web pages don’t have access to this interface (for good reason, as there is otherwise potential for this to be abused). Although web apps don’t have access, Chrome extensions do. Chrome Extensions won’t work in other browsers. But at the time of this writing Chrome accounts for 67% of the browser market share and Microsoft has announced that they will use Chromium as the foundation for their Edge browser. While this UDP socket implementation isn’t available in a wide range of browsers, it is largely available to a wide range of users since this is the browser of choice for most desktop users.

To run HTML code as an extension there are two additional elements that are needed: a manifest and a background script. The background script will create a window and load the starting HTML into it.

chrome.app.runtime.onLaunched.addListener(function() {

chrome.app.window.create('index.html', {

'outerBounds': {

'width': 600,

'height': 800

}

});

});

I won’t go into a lot of detail about what is in the manifest, but I will highlight its most important elements. The manifest is in JSON format. The initial scripts to be run are defined app.background.scripts. Other important elements are the permission element, without which the attempts to communicate over UDP or join a multicast group will fail and the manifest_version element. The other elements are intuitive.

{

"name": "SSDP Browser",

"version": "0.1",

"manifest_version": 2,

"minimum_chrome_version": "27",

"description": "Discovers SSDP devices on the network",

"app": {

"background": {

"scripts": [

"./scripts/background.js"

]

}

},

"icons": {

"128": "./images/j2i-128.jpeg",

"64": "./images/j2i-64.jpeg",

"32": "./images/j2i-32.jpeg"

},

"permissions": [

"http://*/",

"storage",

{

"socket": ["udp-send-to", "udp-bind", "udp-multicast-membership"]

}

]

}

Google already has a wrapper available as a code example chrome.udp.sockets that was published for using Multicast on a network. In it’s unaltered form the Google code sample assumes that text is encoded in the 16-bit character encoding of Unicode. SSDP uses 8-bit ASCII encoding. I’ve taken Google’s class and have made a small change to it to use ASCII instead of Unicode.

To perform the SSDP search the following steps are performed.

- Create a UDP port and connect it to the multicast group 239.255.255.250

- Send out an M-SEARCH query on port 1900

- wait for incoming responses originating from port 1900 on other devices

- Parse the response

- Stop listening after some time

The first item is mostly handled by the Google Multicast class. We only need to pass the port and address to it. The M-SEARCH query is a string. As for the last item, it isn’t definitive when responses will stop coming in. Some devices appear to occasionally advertise themselves to the network even if not requested. In theory you could keep getting responses. At some time I’d suggest just no longer listening. Five to ten seconds is usually more than enough time. There are variations in the M-SEARCH parameters but the following can be used to ask for all devices. There are other queries that can be used to filter for devices with specific functionality. The following is the string that I used; what is not immediately visible, is that after the last line of text there are two blank lines.

M-SEARCH * HTTP/1.1

HOST: 239.255.255.250:1900

MAN: "ssdp:discover"

MX: 3

ST: ssdp:all

USER-AGENT: Joel's SSDP Implementation

When a response comes in, the function that we assign to MulticastScoket.onDiagram will be called with a byte array containing the response, the IP address from which the response came, and the port number from which the response was sent (which will be 1900 for our current application). In the following code sample, I initiate a search and print the responses to the JavaScript console.

const SSDP_ADDRESS = '239.255.255.250';

const SSDP_PORT = 1900;

const SSDP_REQUEST_PAYLOAD = "M-SEARCH * HTTP/1.1\r\n"+

"HOST: 239.255.255.250:1900\r\n"+

"MAN: \"ssdp:discover\"\r\n"+

"MX: 3\r\n"+

"ST: ssdp:all\r\n"+

"USER-AGENT: Joel's SSDP Implementation\r\n\r\n";

var searchSocket = null;

function beginSSDPDiscovery() {

if (searchSocket)

return;

$('.responseList').empty();

searchSocket = new MulticastSocket({address:SSDP_ADDRESS, port:SSDP_PORT});

searchSocket.onDiagram = function(arrayBuffer, remote_address, remote_port) {

console.log('response from ', remote_address, " ", remote_port);

var msg = searchSocket.arrayBufferToString8(arrayBuffer);

console.log(msg);

}

searchSocket.connect({call:function(c) {

console.log('connect result',c);

searchSocket.sendDiagram(SSDP_REQUEST_PAYLOAD,{call:()=>{console.log('success')}});

setTimeout(endSSDPDiscovery, 5000);

}});

}

Not that parsing the response strings is difficult, by any means it would be more convenient if the response were a JSON object. I’ve made a function that will do a quick transform on the response so I can work with it like any other JSON object.

function discoveryStringToDiscoveryDictionary(str) {

var lines = str.split('\r');

var retVal = {}

lines.forEach((l) => {

var del = l.indexOf(':');

if(del>1) {

var key = l.substring(0,del).trim().toLowerCase();

var value = l.substring(del+1).trim();

retVal[key]=value;

}

});

return retVal;

}

After going through this transformation a Roku Streaming Media Player on my network returned the following response. (I’ve altered the serial number)

{

cache-control: "max-age=3600",

device-group.roku.com: "D1E000C778BFF26AD000",

ext: "",

location: "http://192.168.1.163:8060/",

server: "Roku UPnP/1.0 Roku/9.0.0",

st: "roku:ecp",

usn: "uuid:roku:ecp:1XX000000000",

wakeup: "MAC=08:05:81:17:9d:6d;Timeout=10" ,

}

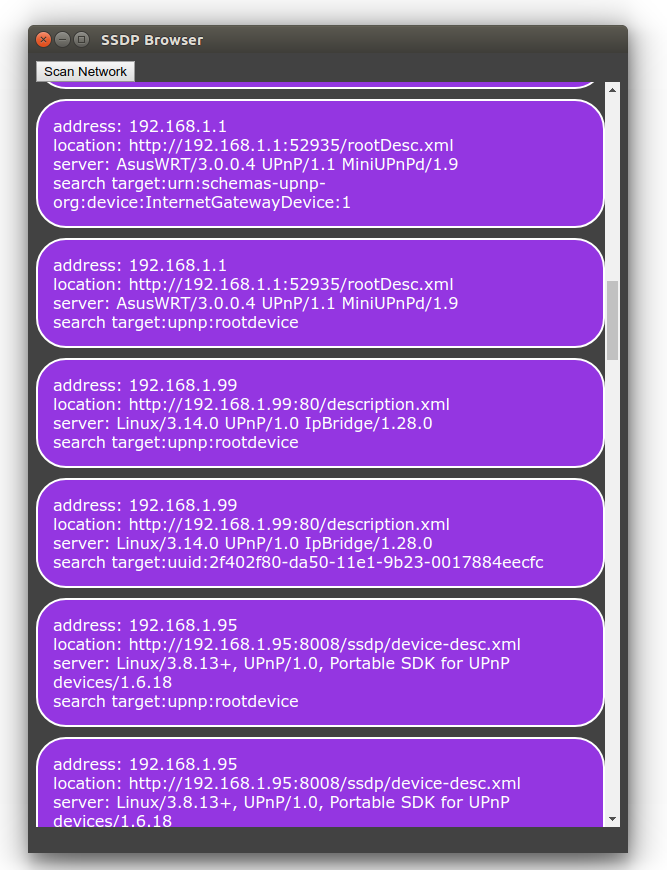

Enough code has been shared for the sample to be used, but rather than rely on the development JavaScript console, I’ll change the sample to show the responses in the UI. To keep it simple I’ve defined the HTML structure that I will use for each result as a child element of a div element of the class palette. This element is hidden, but for each response I’ll clone the div element of the class ssdpDevice; will change some of the child members; and append it to a visible section of the page.

The altered function for that will now display the SSDP responses in the HTML is the following.

function beginSSDPDiscovery() {

if (searchSocket)

return;

$('.responseList').empty();

searchSocket = new MulticastSocket({address:SSDP_ADDRESS, port:SSDP_PORT});

searchSocket.onDiagram = function(arrayBuffer, remote_address, remote_port) {

console.log('response from ', remote_address, " ", remote_port);

var msg = searchSocket.arrayBufferToString8(arrayBuffer);

console.log(msg);

discoveryData = discoveryStringToDiscoveryDictionary(msg);

console.log(discoveryData);

var template = $('.palette').find('.ssdpDevice').clone();

$(template).find('.ipAddress').text(remote_address);

$(template).find('.location').text(discoveryData.location);

$(template).find('.server').text(discoveryData.server);

$(template).find('.searchTarget').text(discoveryData.st)

$('.responseList').append(template);

}

searchSocket.connect({call:function(c) {

console.log('connect result',c);

searchSocket.sendDiagram(SSDP_REQUEST_PAYLOAD,{call:()=>{console.log('success')}});

setTimeout(endSSDPDiscovery, 5000);

}});

}